(WIP) Some Secrets Shared

Published:

In cryptography, secret sharing is the process of splitting a secret into pieces, called secret shares, so that no individual device stores the original secret but some group of devices can collectively recover that secret. Classic examples of situations involving secret sharing include missile launch codes and shared custody in the corporate setting; in both cases multiple individuals’ authorizations are required before any action can be taken. Recently, secret sharing has seen extensive use within multi-party computation (MPC) involving secret data, and private key management, where an individual or organization has cryptocurrency belonging to a secret key and they wish to split this key into \(n\) key shares such that some subset of \(t\) shares are required for using the key.

In this post, we will be discussing two forms of secret sharing: Replicated Secret Sharing (RSS) and Shamir Secret Sharing (SSS). We will introduce the details of both of these schemes assuming relatively little background. We will also introduce a process for converting RSS shares into SSS shares that can be employed to construct a scheme known as Pseudorandom Secret Sharing (PSS) in which a single setup leads to an arbitrary number of secure deterministic SSS instantiations. Finally, we will see these constructions in action in the threshold Schnorr signature scheme, Arctic.

Table of Contents

- 2-of-3 Secret Sharing Examples

- Shamir Secret Sharing

- Lagrange Interpolation

- Uniqueness of Polynomial Interpolation

- Replicated Secret Sharing

2-of-3 Secret Sharing Examples

Suppose we wish to split a secret, \(s\), into \(n=3\) pieces, \((s_1, s_2, s_3)\) such that any \(t=2\) secret shares can be used to recover the original secret. For clarity and simplicity, say that we wish to distribute secret shares to three parties, Alice (A), Bob (B), and Carol (C).

One approach is to begin by splitting up the secret into three shares that add up to \(s\). For example, we could pick \(s_1\) and \(s_2\) randomly and then set \(s_3 = s - s_1 - s_2\). This gives us three secret shares such that all three are required to recover our secret; knowing any two secret shares yields no information about \(s\) since it is still equally likely to be any number. Next, we can turn this \(t=3\) scheme into a \(t=2\) scheme by making our secret shares collections of these pieces. Namely, we give Alice the set \(\{s_2, s_3\},\) we give Bob the set \(\{s_1, s_3\},\) and we give Carol the set \(\{s_1, s_2\}\). No individual has any information about \(s\), but if any two of them collaborate, they will collectively know all three summands!

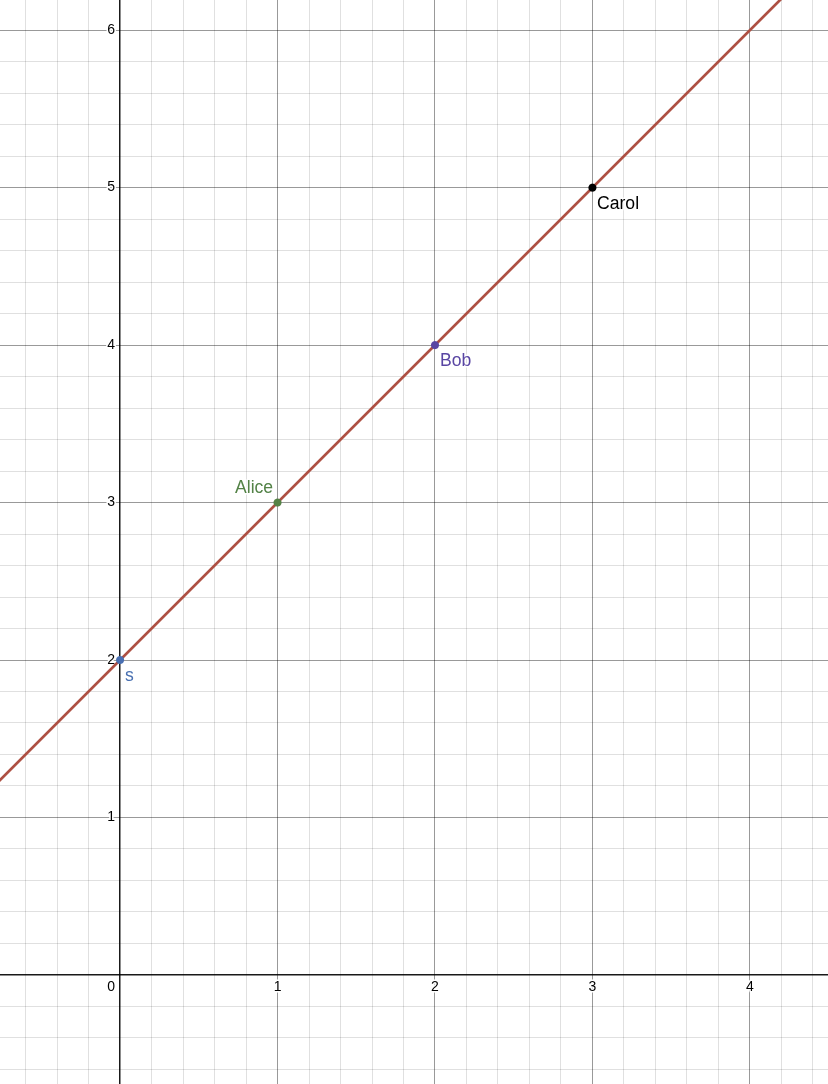

An alternative approach is to use the fact that any two points define an entire line. Thus, if we work in the standard 2-dimensional plane and pick one point to be \((0, s)\), and we pick a second point to have a random second coordinate, \((1, s_1)\), then these two points uniquely define a line on which must contain some points \((2, s_2)\) and \((3, s_3)\) for some values of \(s_2\) and \(s_3\). Once we have chosen \(s_1\) at random there are even nice formulas for our other values that can be derived from very elementary means. For example, we know the slope of this line is \(\frac{s_1 - s}{1 - 0} = s_1 - s\) so that

\[s_2 = s_1 + (s_1 - s) = 2s_1 - s\]and

\[s_3 = s_2 + (s_1 - s) = 2s_1 - s + (s_1 - s) = 3s_1 - 2s.\]

Hence, if we give \((1, s_1)\) to Alice, \((2, s_2)\) to Bob, and \((3, s_3)\) to Carol then any two of them will be able to collaborate to compute the line going through their two points, and will be able to discover \(x\) by computing the value of the second coordinate when the first coordinate is equal to \(0\). Furthermore, no individual participant has any information at all about the value of \(s\).

Shamir Secret Sharing

Using lines as in our example above works great for any scheme where \(t=2\) meaning that any two participants can learn the secret, but what if you wanted to do something similar to construct a scheme where \(t=3\) participants must collaborate to recover the secret? As it turns out, there is a curve that is uniquely determined by any three of its points: a parabola! More generally, for any number \(t\), a degree \((t-1)\) polynomial is a curve which is uniquely determined by any $t$ of its points. We justify this claim below. Furthermore, knowledge of any \(t-1\) points yields no information about any other points on the curve assuming that the curve was generated randomly.

In other words, if we want to do a \(t\)-of-\(n\) secret sharing of \(s\), we choose random values \(a_1, a_2,\ldots, a_{t-1}\) and use these to define a polynomial

\[f(x) = s + a_1x + a_2x^2 + \cdots + a_{t-1}x^{t-1}.\]Because we set the constant term to \(s\), we have that \(f(0) = s\). Next, we set \(s_1 = f(1), s_2 = f(2), \ldots, s_n = f(n)\) and distribute the values \((1,s_1), (2, s_2), \ldots, (n, s_n)\) to their respective parties. Finally, any \(t\) parties can use their shares to reconstruct the polynomial \(f(x)\), because it is determined by any \(t\) of its points, and then they can compute \(s = f(0)\). This scheme is called Shamir Secret Sharing (SSS) (TODO: foreshadow DKG/VSS). But how do we actually compute \(f(x)\) from some set of \(t\) points \((x_1, y_1), (x_2, y_2), \ldots, (x_t, y_t)\)? The problem of computing a curve that fits a given set of points is known as interpolation and is discussed in the next section. For readers already familiar with the details of Lagrange interpolation, skip ahead.

Lagrange Interpolation

Let’s begin with the example of trying to compute a line (where \(t=2\)) given two points: \((x_1, y_1)\) and \((x_2, y_2)\). The slope of our line is \(\frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1}\), and thus we can use the point \((x_1, y_1)\) along with this slope to write down the so-called point-slope form of the line:

\[y - y_1 = \left(\frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right)(x - x_1).\]However, in its current form, this equation does not generalize particularly nicely to higher degree polynomials, so let us try to rewrite this equation with the goal of having more symmetry between how \(x_1\) and how \(x_2\) is used. After all, we could have just as easily used the other point for our point-slope form to get the equivalent line \(y - y_2 = \left(\frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right)(x - x_2).\) As a first step, we isolate \(y\) and separate the \(x\) terms from the \(y_1\)s and \(y_2\)s, and then we distribute and factor out \(y_1\):

\[\begin{align*} y - y_1 &= \left(\frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right)(x - x_1)\\ y &= \left(\frac{x-x_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right)(y_2 - y_1) + y_1\\ &= y_2\left(\frac{x-x_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right) - y_1\left(\frac{x-x_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right) + y_1\\ &= y_2\left(\frac{x-x_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right) + y_1\left(1 - \frac{x-x_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right)\\ &= y_2\left(\frac{x-x_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right) + y_1\left(\frac{x_2 - x_1}{x_2 - x_1} - \frac{x-x_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right)\\ &= y_2\left(\frac{x-x_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right) + y_1\left(\frac{x_2 - x}{x_2 - x_1}\right)\\ &= y_2\left(\frac{x-x_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right) + y_1\left(\frac{x - x_2}{x_1 - x_2}\right) \end{align*}\]The result is a much more symmetric equation that is also relatively easy to understand. If we plug in \(x = x_1\), then we get

\[y = y_2\left(\frac{x_1 - x_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right) + y_1\left(\frac{x_1 - x_2}{x_1 - x_2}\right) = y_2\cdot 0 + y_1\cdot 1 = y_1.\]Meanwhile, if we plug in \(x = x_2\), then we get

\[y = y_2\left(\frac{x_2 - x_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right) + y_1\left(\frac{x_2 - x_2}{x_1 - x_2}\right) = y_2\cdot 1 + y_1\cdot 0 = y_2.\]Thus, it appears what is really going on is that we have these “building block” lines, \(L_2(x) = \frac{x - x_1}{x_2 - x_1}\) and \(L_1(x) = \frac{x - x_2}{x_1 - x_2}\), which are equal to either \(0\) or \(1\) when we plug in \(x_1\) or \(x_2\). For example, \(L_2(x_1)\) is equal to \(0\) when we plug in \(x_1\) because the numerator is clearly \(0\), while when we plug in \(x_2\) the denominator of \(L_2(x_2)\) is equal to the numerator causing the value to be \(1\), and in this case this building block is multiplied by \(y_2\) in the function above so that we get to multiply this \(1\) by \(y_2\) getting us the desired result since \(y = y_2\cdot L_2(x) + y_1\cdot L_1(x).\)

With this example in mind, how might we build similar building blocks for a parabola given three points \((x_1, y_1), (x_2, y_2),\) and \((x_3, y_3)\)? In particular, say that we want to construct a new parabola \(L_1(x)\) such that \(L_1(x_1) = 1, L_1(x_2) = 0\) and \(L_1(x_3) = 0\)? To achieve our two \(0\) values, we can begin with the parabola \(y = (x - x_2)(x - x_3)\), and then to ensure that \(L(x_1) = 1\), we can divide this parabola by its current value when \(x_1\) is plugged in giving us

\[L_1(x) = \frac{(x - x_2)(x - x_3)}{(x_1 - x_2)(x_1 - x_3)}.\]Similarly, we can define \(L_2(x) = \frac{(x - x_1)(x - x_3)}{(x_2 - x_1)(x_2 - x_3)}\) and \(L_3(x) = \frac{(x - x_1)(x - x_2)}{(x_3 - x_1)(x_3 - x_2)}.\) Finally, we can define our parabola

\[\begin{align*} f(x) &= y_1\cdot L_1(x) + y_2\cdot L_2(x) + y_3\cdot L_3(x)\\ &= y_1\cdot \frac{(x - x_2)(x - x_3)}{(x_1 - x_2)(x_1 - x_3)} + y_2\cdot \frac{(x - x_1)(x - x_3)}{(x_2 - x_1)(x_2 - x_3)} + y_3\cdot \frac{(x - x_1)(x - x_2)}{(x_3 - x_1)(x_3 - x_2)}. \end{align*}\]That sure is a mouthful! And it is only going to keep getting bigger, so let’s introduce some notation to make things more compact. Suppose we have a set of participant indices, \(C = \{x_1, x_2, x_3\}\), then for a fixed number \(i\), the building block \(L_i(x)\) that is \(1\) at \(x_i\) and \(0\) for the other values in \(C\) can be described using the following product notation:

\[L_i(x) = \prod_{x_j\in C\setminus\{x_i\}} \frac{x - x_j}{x_i - x_j}.\]In other words, for every \(x_j\in C\) that is not \(x_i\), we multiply in a factor of \(\frac{x - x_j}{x_i - x_j}\). Next, we can concisely write \(f(x)\) using the summation notation:

\[f(x) = \sum_{i=1}^3 y_i\cdot L_i(x).\]This notation simply reads that for every value of \(i\) from \(1\) to \(3\), we add in a summand of the form \(y_i\cdot L_i(x)\) for that value of \(i\). In total, we can now write

\[f(x) = \sum_{i=1}^3 y_i\prod_{x_j\in C\setminus\{x_i\}}\frac{x - x_j}{x_i - x_j}.\]This final form of \(f(x)\) is finally something that we can generalize to arbitrary degree polynomials. If we are given \(t\) points \((x_1, y_1),\ldots, (x_t, y_t)\) then we can compute the unique degree \(t-1\) polynomial that goes through these points as

\[f(x) = \sum_{i=1}^t y_i \prod_{x_j\in C\setminus\{x_i\}}\frac{x - x_j}{x_i - x_j},\]where \(C = \{x_1,\ldots, x_t\}\) is the set of \(x\)-coordinates/participant indices. This polynomial goes through the point \((x_k, y_k)\) for every \(k\) because if we plug in \(x_k\) for \(x\), all but one of the summands is equal to \(0\) (because of the \(x - x_k\) factor in the numerator), and the only summand that does not equal \(0\) is the one corresponding to when \(i = k\), in which case the product is equal to \(1\) so that \(f(x_k) = y_k\cdot 1\).

This particular method of reconstructing a polynomial from its points is known as Lagrange interpolation and the “building blocks” that we used, \(L_i(x)\), are known as Lagrange polynomials.

Uniqueness of Polynomial Interpolation

While it is completely sufficient for all practical purposes to simply assume/believe/trust that \(t\) points uniquely define a degree \((t-1)\) polynomial, most arguments for why this must be the case are not particularly difficult (though they can be a bit dense), so I’ve included one such argument here just for fun. No content from this section is required to read the rest of this post.

We wish to prove the claim that if \(f(x)\) and \(g(x)\) are two polynomials of degree \(t-1\), and \(f(x_i) = g(x_i)\) for \(t\) distinct values of \(x_i\), then \(f(x) = g(x)\) as polynomials. The difference of two polynomials of degree \((t-1)\) is of degree at most \((t-1)\), so that \(h(x) = f(x) - g(x)\) is a polynomial of degree at most \((t-1)\) such that its output is \(0\) when evaluated at any of the \(t\) input values \(x_i\). Such an input that causes a function to be evaluated to zero is called a root of that function. Therefore, it is sufficient to prove that if a degree \((t-1)\) polynomial, \(h(x)\), has \(t\) distinct roots, then \(h(x) = 0\) (in our case this would imply that \(f(x) - g(x) = 0\Rightarrow f(x) = g(x)\)).

Equivalently, we can show that if \(h(x)\) is a non-zero polynomial of degree at most \((t-1)\), then it can have at most \((t-1)\) roots (as this implies that having more roots makes \(h(x)\) into the zero function). If \(t = 1\), then \(h(x)\) is a polynomial of degree at most \(t-1 = 1-1 = 0\) so that \(h(x)\) is a constant non-zero value (since we are assuming that \(h(x)\neq 0\)) and thus it has no roots. If \(t = 2\), then \(h(x)\) is of degree at most \(t-1 = 2-1 = 1\) making it a non-zero line or a non-zero constant function, both of which have at most \(1\) roots. We now continue our argument using induction.

Suppose every non-zero polynomial of degree at most \((n-1)\) has at most \((n-1)\) roots; we wish to show that this implies that every non-zero polynomial of degree \(n\) has at most \(n\) roots. Let \(h(x)\) be an arbitrary non-zero degree \(n\) polynomial. If \(h(x)\) has no roots, then it has fewer than \(n\) roots and we are done. Otherwise, there is some value \(a\) such that \(h(a) = 0\). Consider the polynomial, \(p(x) = h(x + a)\), that is the result of plugging in \((x+a)\) for \(x\). This is a new polynomial of degree at most \(n\). Furthermore, we have that \(p(0) = h(0 + a) = h(a) = 0\) from which we can conclude that every term of \(q(x)\) (in its expanded form) is divisible by \(x\) so that we can factor this out to get that \(p(x) = x\cdot q(x)\) for some polynomial \(q(x)\) of degree at most \((n-1)\). Finally, we can use the fact that

\[h(x) = h((x-a) + a) = p(x-a) = (x-a)\cdot q(x-a)\]to see that \(h(x)\) is equal to \((x-a)\) times a polynomial of degree at most \((n-1)\), which must have at most \((n-1)\) roots by our inductive hypothesis, so that we can conclude that \(h(x)\) has at most \(n\) roots, as desired.

To summarize, we have shown that if a polynomial, \(h(x)\), has a root, \(a\), then \(h(x) = (x-a)\cdot q(x)\) for some polynomial, \(q(x)\), of lesser degree; hence, by induction, it is clear to see that all non-zero polynomials of degree at most \((t-1)\) have at most \((t-1)\) roots, and thus if \(h(x) = f(x) - g(x)\) has \(t\) roots (since \(f(x)\) and \(g(x)\) agree on \(t\) distinct values), we can conclude that \(h(x) = f(x) - g(x) = 0\Rightarrow f(x) = g(x)\).

Replicated Secret Sharing

Recall from our 2-of-3 example at the beginning of this post that there is another way to construct a secret sharing scheme by creating a set of additive secrets, which are random subject to the constraint that the sum of all of the additive secrets is the original secret value, and then sharing some subset of these secrets with each participant in such a way that any \(t\) of them collectively know all of the secrets. This idea can be formalized and generalized in the following way:

For each subset \(a_i\subseteq \{1,2,\ldots, n\}\) of size \(t-1\), create a secret value \(\phi_i\), where all but one of these values is chosen randomly and the final value is chosen so that the sum of all of the \(\phi_i\) is equal to the secret, \(s\). Share the value \((\phi_i, a_i)\) with each member whose index is not in \(a_i\). In other words, for every “maximally unqualified subset” of participants, which are the subsets of size \(t-1\), create a secret known to everyone not in that group of \(t-1\) participants. This guarantees that \(t\) participants are required to recover the secret as any \(t-1\) participants collectively do not know one of the secrets. Furthermore, every \(t\) participants do collectively know all of the secrets, since at least one of the \(t\) must be in the complement of any subset \(a_i\) of size \(t-1\).

For example, say that you wanted to perform a \(3\)-of-\(4\) secret sharing between Alice (\(1\)), Bob (\(2\)), Carol (\(3\)), and Dave (\(4\)). Then we begin by enumerating all of the subsets of \(\{1,2,3,4\}\) of size \(3-1=2\):

\[\begin{align*} a_1 &= \{1,2\},\\ a_2 &= \{1,3\},\\ a_3 &= \{1,4\},\\ a_4 &= \{2,3\},\\ a_5 &= \{2,4\},\\ a_6 &= \{3,4\}. \end{align*}\]Next, we compute \(6\) corresponding values \((\phi_1, \phi_2, \phi_3, \phi_4, \phi_5, \phi_6)\) that sum to \(s\) by picking \(\phi_1\) through \(\phi_5\) at random and then setting \(\phi_6 = s - \sum_{i=1}^5\phi_i\). Finally, \((\phi_1, a_1)\) is given to Carol and Dave, \((\phi_2, a_2)\) is given to Bob and Dave, \((\phi_3, a_3)\) is given to Bob and Carol, \((\phi_4, a_4)\) is given to Alice and Dave, \((\phi_5, a_5)\) is given to Alice and Carol, and \((\phi_6, a_6)\) is given to Alice and Bob. In the end, Alice knows \(\{\phi_4, \phi_5, \phi_6\}\), Bob knows \(\{\phi_2, \phi_3, \phi_6\}\), Carol knows \(\{\phi_1, \phi_3, \phi_5\}\), and Dave knows \(\{\phi_1, \phi_2, \phi_4\}\). As a result, any two of them collectively are missing one of the secrets and hence know no information about \(s\), while any three of them collectively know all of the secrets and can recover \(s\).

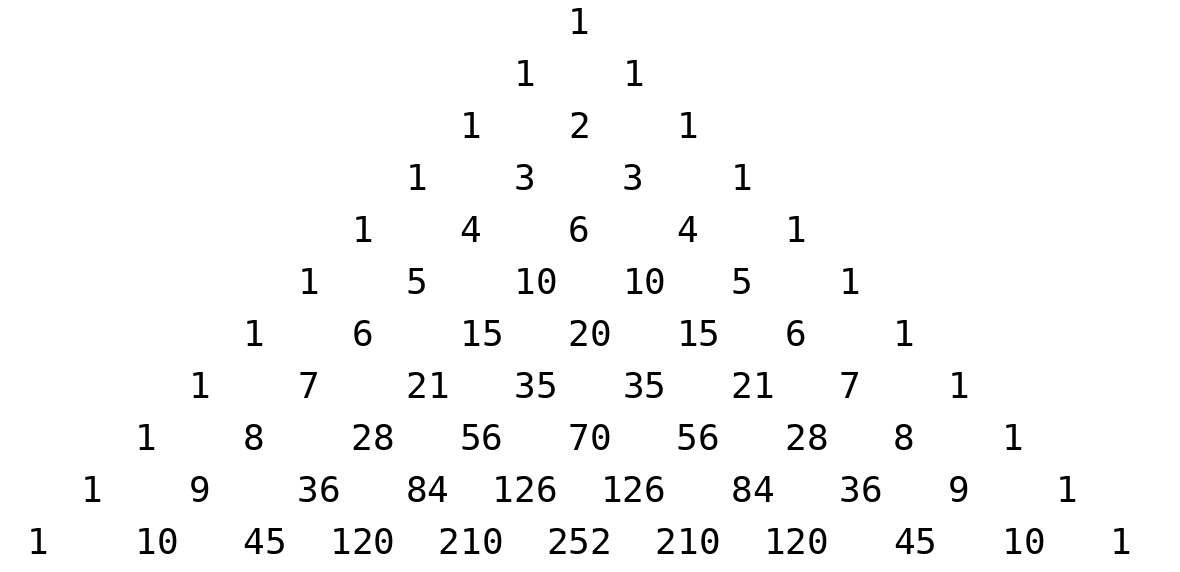

You may notice that while a \(2\)-of-\(3\) replicated secret sharing (RSS) scheme only required \(3\) secret summands, where each participant was given \(2\), our \(3\)-of-\(4\) example required \(6\) secret summands, where each participant was given \(3\). In general, the total number of secret summands in a \(t\)-of-\(n\) RSS scheme is the number of subsets of \(\{1,2,\ldots, n\}\) of size \(t-1\), which is denoted by \(\binom{n}{t-1}\) (pronounced \(n\) “choose” \(t-1\)), and each participant receives each summand corresponding to a subset of size \(t-1\) not containing themselves, of which there are \(\binom{n-1}{t-1}\). This is somewhat grave news for RSS, especially compared to SSS above where each party receives a single number. The value of \(\binom{n}{t}\) (depicted below with \(n\) corresponding to rows and \(t\) corresponding to diagonal columns) grows exponentially large with \(n\) unless \(t\) stays bounded or unless \(n-t\) stays bounded (and even in these cases the values still grow large).

Thus, despite the simplicity of RSS, it is no big surprise that SSS has become the default method of secret sharing. However, in many practical applications, such as private key management, the number of devices involved (\(n\)) is relatively small. For example, even if \(10\) devices are used, then in the worst case we require \(\binom{10}{5} = 252\) summands, \(\binom{9}{5} = 126\) of which are known to each device so that if each secret number is \(32\) bytes, then each party only needs to store approximately \(4\) kilobytes of data. Meanwhile, the worst case for \(20\) devices requires each device to store approximately \(3\) megabytes of data. It is clear that RSS scales poorly to large numbers of devices, but it is still perfectly practical to use for relatively small numbers of signers such as these.

One benefit that RSS has, which SSS does not, is that if we are sharing many randomly generated secrets, then rather than setting up a new sharing for each secret we can instead perform a RSS setup a single time and treat each of the secret summands as a key to a pseudo-random function (PRF). Subsequently, we can non-interactively generate an unlimited number of RSS-shared secrets deterministically. TODO: Unpack this.